-

Romanticism and Representation: Watercolour Painting in the Nineteenth Century

Exhibition Article - 'Works on Paper' -

Watercolours consistently feature within our areas of specialism at Rountree Tryon Galleries. The genres of wildlife, maritime, and topographical painting all owe a great deal to the versatility of watercolour – from wildlife illustrations to polar scenes painted aboard vessels. This article explores the views of watercolour painting in arguably its finest period, the nineteenth century, and the ways in which this background can inform our understanding and appreciation of the watercolours currently available in our Works on Paper show, running from 13-25 March.

-

J.M.W Turner (1775-1851), The Lake of Lucerne from Brunnen (c. 1840s), sold at Sotheby's, London, for £2 million on 4 July 2018.

J.M.W Turner (1775-1851), The Lake of Lucerne from Brunnen (c. 1840s), sold at Sotheby's, London, for £2 million on 4 July 2018. -

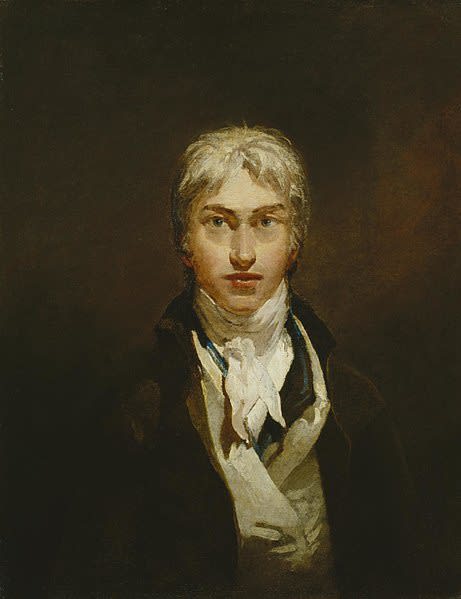

J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851), Self Portrait, c. 1798-9 (Tate Britain), image in the public domain.

J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851), Self Portrait, c. 1798-9 (Tate Britain), image in the public domain. -

Paintings such as Alfred Herbert’s Saint-Malo from the Harbour, currently on display in our Works on Paper show, captures Ruskin’s evocation of speed and freedom in the painting of watercolours en plein air. Herbert has layered washes of paint to create the clouds, warm sky, and reflections in the low water. The town is almost silhouetted against the sky, maintaining a hazy quality against which the beached tall ship and colourful figures, painted in gouache, are thrown into relief. The use of sgraffito, a scratching out of the paint, in the lower portion of the work not only adds highlights to the scene but also reminds us of the materiality of the picture. The paper shines through, asserting the hand of the artist and the process its creation. The painting is an impression of a moment in time, with a clear sense of the interaction between the artist’s experience of the environment and his immediate response on paper.

-

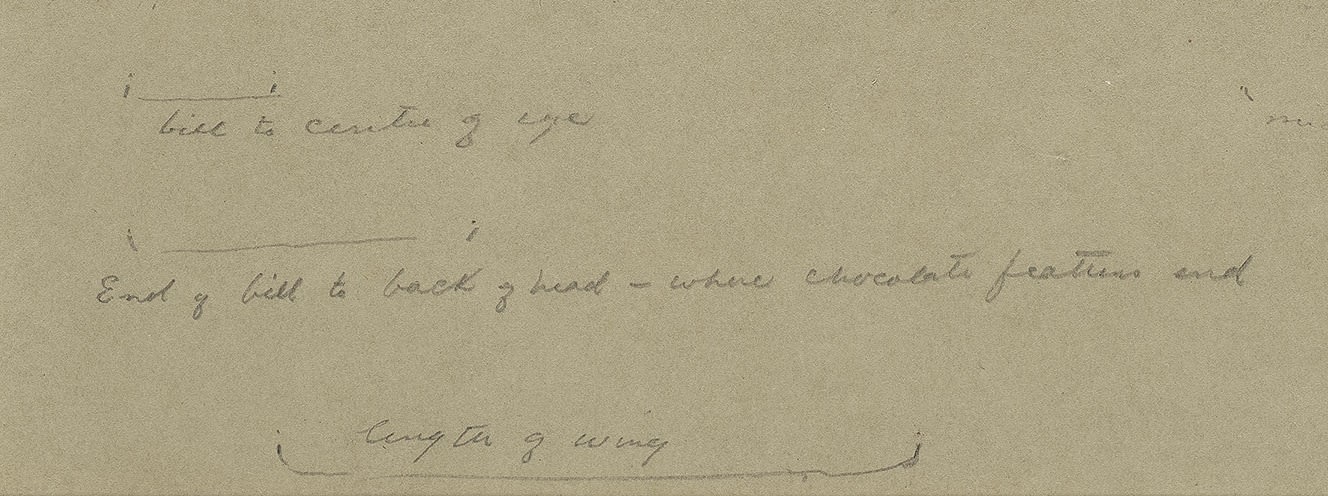

Archibald Thorburn’s studies offer an alternative perspective on the use of watercolour and gouache. Rather than an impression of a scene, the studies instead reflect the mind of an artist working through anatomical detail and the ways in which he can bend the medium to the purpose of representation. Thorburn established his reputation as a foremost wildlife artist when he was commissioned to illustrate Lord Lilford’s Coloured Figures of the Birds of the British Islands (1885-1897). In his Tree sparrow studies, also currently on display in the gallery, the artist’s process is directly shown in his accompanying notes on colour and dimension. In the lower-left corner, he has drawn lines which are then labelled ‘bill to centre of eye’, ‘End of bill to back of head – where chocolate features end’, and ‘length of wing’. The study of the sparrow’s head at the top of the paper shows these observations in practice, as Thorburn navigates colour, scale, and proportion to compose a highly accurate image of the bird. Unlike the freedom, effortlessness, and selflessness that Ruskin admired in Turner, this process is highly considered and scientific. Nonetheless, it stands as a fascinatingly personal artwork which demonstrates the versatility of the medium.

Archibald Thorburn’s studies offer an alternative perspective on the use of watercolour and gouache. Rather than an impression of a scene, the studies instead reflect the mind of an artist working through anatomical detail and the ways in which he can bend the medium to the purpose of representation. Thorburn established his reputation as a foremost wildlife artist when he was commissioned to illustrate Lord Lilford’s Coloured Figures of the Birds of the British Islands (1885-1897). In his Tree sparrow studies, also currently on display in the gallery, the artist’s process is directly shown in his accompanying notes on colour and dimension. In the lower-left corner, he has drawn lines which are then labelled ‘bill to centre of eye’, ‘End of bill to back of head – where chocolate features end’, and ‘length of wing’. The study of the sparrow’s head at the top of the paper shows these observations in practice, as Thorburn navigates colour, scale, and proportion to compose a highly accurate image of the bird. Unlike the freedom, effortlessness, and selflessness that Ruskin admired in Turner, this process is highly considered and scientific. Nonetheless, it stands as a fascinatingly personal artwork which demonstrates the versatility of the medium. -

-

Nineteenth century watercolours, from studies to finished works and from maritime scenes to wildlife paintings, have enduring appeal. Watercolour can capture unique qualities of both environment and artist, often evoking a sense of speed and effortless, as well as serving as a medium of representational truth - particularly with the addition of details in gouache. The works discussed are on display in our Works on Paper show in our Petworth gallery until 25 March. Instillation views, a list of works, and a digital catalogue can all be found under the exhibitions tab on our website.

by Lydia Gascoigne, Gallery Specialist -

Bibliography

John Ruskin, The Elements of Drawing (London: Routledge, 1857), p. 385

Ed. by E.T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn, The Works of John Ruskin (London: George Allen, 1903)

Ed. by Alison Smith, Watercolour, exhibition catalogue (London: Tate Publishing, 2011), p. 9